I didn’t meet Dr. Lemle. I was eight years old when he passed away in 1978, and my family did not attend the ARI synagogue. I was a student at a leftwing school, learned Yiddish there, and attended Shomer Hatzair. I knew the stories from the Bible as historical accounts and folklore events. The parties were opportunities to get together with the family and eat delicacies from recipes inherited from a remote past in Eastern Europe. God or religion has never been a big issue.

But Dr. Lemle – this is how I would have addressed him, like everyone else who enjoyed his acquaintance – changed my life! Having access to the philosophy and ideals of Reform Judaism through its spiritual and secular leaders, congregants and activities, when I approached ARI in the 1980s, enchanted me.

Lemle’s legacy – Lemle is what I call him intimately in my research – transcends his contemporaries and generations. Imprisoning him in his lifetime or exclusively in his rabbinical activities would be an irreparable mistake for the history of the presence of Jews in Brazil and would reduce their role in Judaism today.

Lemle’s life should not be recounted as a continuous thread of suffering; suffering is inherent to the situations he and many of his contemporaries went through – segregation, imprisonment, exile. But each stage of his life consolidates a stage of his vision, which he incessantly transformed into a mission. ARI is a concrete expression of its community and congregational vision.

In a document from early 1972, Lemle addresses the themes of the liturgy as they were instituted at the founding of the ARI in the 1940s, which in turn were inherited from the tradition of German Reform Judaism. Lemle, however, corroborates the adjustments that have been made over the years because “the situation of modern life has brought technical problems in relation to certain determinations of tradition. We cannot deceive ourselves about the fact that most of our congregants drive on Shabbat. Our orientation was thus determined: everything that contributes to the true beauty of Shabbat, Oneg Shabbat, will have to be admitted.” And he emphasizes, “we have no other guidance than this: whatever inspires us for Kiddush Hachaim, the sanctification of life, the sanctification of our feelings and the sanctification of our relationships with others – this is the day of Shabbat. And in this way, we also achieve what seems so difficult to modern human beings, the most personal relationship with what is the Supreme Order, with the Supreme Being, with God.” This blunt stance is what makes it so natural and indisputable, in these challenging times of pandemic, to come together through available technologies.

Lemle was born on October 30, 1909 in the small village Fischach, in southern Germany. Lemle witnessed the arrival of Jewish moneylenders and traveling salesmen from Eastern Europe speaking Yiddish and bringing trinkets and lots of news and novelties, not those from newspapers, but the social ones: lists of single girls, offers and demands, deaths, the behind the scenes. In a universe of approximately 500 thousand German Jews, at the beginning of the 1930s there were around 50 thousand Polish Jews living in German territory.

He focused his work on spreading the message of liberal Judaism, welcoming new origin groups, and less on ethnic separations

Upon arriving in Brazil in December 1940, Lemle came across an Ashkenazi Jewish community predominantly from Eastern Europe: Poles, Russians, Lithuanians. Now they were the majority! He made this an encouragement to his mission, not an obstacle: he learned Yiddish! He focused his work on spreading the message of liberal Judaism, welcoming new origin groups, and less on ethnic separations. In addition to strong ties of friendship with Eastern European Jews, it was also among Moroccan and Portuguese Jews, already established and integrated, that Lemle found interlocutors in his country of exile.

In his book “O Drama Judaico”, from 1944, defined at the time as the first book written in Brazil by a Jew about Jews, Lemle expresses gratitude: “For several generations, congregations of Brazilian Israelites have flourished in the Center and North of the country, undisturbed in observing their religion. These sons of Brazil achieved respected positions in Brazilian society and economy, while at the same time standing out for their loyalty to the Israelite faith. They made, in this visible way, another trait of the truly democratic character of this country; Fidelity to the Jewish religion did not in any way prevent them from being classified among the most patriotic children of Brazil.”

Lemle married in May 1934 his cousin, Margot Rosenfeld – their mothers were sisters. Margot’s father may have been one of the first two fatal victims of the National Socialist regime. In March 1933, four young men were beaten in Creglingen, two of them died. According to Prof. Dr. Rupp of the University of Würzburg, if “there were a list of names of the more than six million Jews murdered, Hermann Stern and Arnold Rosenfeld would rank at the top as the first victims of the Shoah.”

Lemle was installed as rabbi in the pulpit of the Mannheim community on April 1, 1933. No one could have predicted, when marking the festive date of his inauguration, that this would be a tragic day for the Jews in Germany: the day of the boycott to Jewish offices, offices and establishments.

His performance in Mannheim was brilliant and notorious. The young Rabbi Dr. Heinrich Lemle, as he was still called before moving to Henrique in Brazil, describes in a 1938 CV: “a few months later Rabbi Dr. Caesar Seligmann visited me and invited me, on behalf of the community’s Board of Directors from Frankfurt, to come to this large and traditional community as a rabbi. I was offered the opportunity to try something unusual. I should work directly with young people as the first Rabbi for the Youth. The Jewish youth of that time experienced their being Jewish as an obstacle to all their future plans.” He takes the pulpit as Rabbi for the Youth in Frankfurt in June 1934.

Lemle lists among his tasks, “classes, counseling, career planning, leadership of youth and scout groups, emigration counseling, counseling for fathers and courses for mothers.” Behind this list of tasks was the most difficult of his career: in addition to his work in the pulpit and in classes, Lemle had to advise families to separate, parents to give up their children and let them go as the only way to save them, and to young people to abandon their dreams of a professional or academic career at renowned German universities and a future of titles and honors, and rather to learn how to drive tractors and work the land for possible immigration to Palestine.

Lemle’s efforts were not in vain. In addition to the success which he personally experienced at ARI until his death in 1978, he was able to collect real evidence of his work throughout his life. In March 1945, a letter [summarized here] that he received from a soldier directly at the front was published in the ARI Bulletin:

Sometimes I wish I could hear your words: here, without a doubt, they are extremely necessary

“Dear Dr. Lemle: You will be surprised to hear from the Western Front, and I do not think you will immediately remember me. I attended your Bar Mitzvah course in 1937. Recently, I read about you in the “Aufbau” [newspaper about survivors and Jewish refugees]. I see that you are continuing, in Brazil, an activity that you started so long ago. Sometimes I wish I could hear your words: here, without a doubt, they are extremely necessary. In 1943, I enlisted in the American Army. I was eager to get into combat and got much of what I wanted when I landed on the beaches of Normandy shortly after the invasion. I learned to live in a hole, always in the shadow of death, into whose hard eyes I looked more than once. War is a horrible thing; I learned to hate it and the Nazis even more because of it. Best regards, Private Fred Karfiol.” Fred died in the United States, aged 66, in December 1990.

What a formidable boost this young soldier gave to the spirits of Lemle and the associated bulletin readers! Especially in the years when the fate of the Jewish people was still uncertain, and the refugees and exiled only had access to sparse and desperate news through those who managed to land here.

In 1935, with the promulgation of racist laws in Germany, the siege closed. The space for coexistence, or even social survival, for Jews was gradually strangled with prohibitions, segregation and censorship. For the German Jew who had an integrated everyday life, a citizen who had been proud or perhaps still proud to belong to that great nation, the message was clear: you are not one of us. You are “der Jude”, the Jew.

For the leaders of Jewish communities in their last throes, managing a contingent under the shock of new circumstances and, in particular, for those who worked directly with the youth, that was a time of equally austere and sensitive action. Lemle’s later work with the youth at ARI, his absolute rigor in offering activities and the inclusion of young people in spheres of community leadership were not just a Jewish value of continuity, of the great link between generations. It was a serious issue of survival. At that moment in Germany, young people were the last chance to save European Jewry and, to do so, they should be sent into the future as in a time capsule.

“The historical evolution of Jewish athletics and sport in Frankfurt am Main is interesting because it reflects a time of extreme resistance and profound problems, which were successfully overcome through personal commitment and determination”, recalls Richard Blum in 1977 in his book about the Bar-Kochba group, an athletic group from Germany’s Maccabi. There is no doubt that Lemle was among those men and women who committed themselves personally. And just like in 1934 and 1935, Frankfurt’s Jewish community held its own Olympic Games in 1936. This time, with special meaning, as it gave those despised in national sport the chance to show off and compete. A note reporting on this great event in the Frankfurt Community Bulletin of January 1937 reads: “During the entry of the athletes for the opening of the third Maccabean International Athletic Games at the Frankfurt hippodrome on November 29, 1936, Rabbi Dr. Lemle emphasized in his speech that the Hebrew words for Aufmarsch and Aufruf have the same root. Thus, an ascendant force of conviviality emerges from the vital and vibrant energy.” Everything leads me to believe that these two words, Aufmarsch – which here means parade – and Aufruf – call, summons –, through the use of the prefix Auf, which in German indicates upward movement, referred to the Hebrew word Aliyah, used for immigration to Israel.

Earlier in 1936, on January 12, at the eulogy for a member of the Frankfurt community, Hermann Schwarz, in the city’s new Jewish cemetery, Lemle already divulges the idea of immigration, of making aliyah, without using the words immigration, Palestine, Israel or others related to the topic. It was a time of extreme observation and suspicion. He highlights in his speech: “It must seem tragic that in his final hour his children were absent and were crying for him far away in another country. But perhaps something lessens the tragedy: for him it was the last and genuine Jewish happiness that family fathers are allowed to experience. While he suffered here on his last bed of pain, while bitter worry filled him – over there in the land of the children a new life, a new future was being founded in which he will continue to live. The last letter from over there could be the reason for his final happiness. (…) thus bridges are built from over there to here, from the land of life, from the land of the children’s future to the resting place of the deceased father.”

1937 is known as a relatively calm year, without major events on the part of the National Socialist government. Racist laws had already been implemented in 1935; the 1936 Olympic Games had already exposed the character traits of the Hitler government to the world. In the eyes of history, 1937 was a year of accommodation and consolidation: the infrastructure of the war was being implemented away from the eyes of public opinion, the National Socialist ideology was thickening and those who could still tried to leave. Or not! The government did not make it very clear what the next steps would be. The great world powers still had a naive belief or a policy of looking the other way, and consciously or cautiously ignored movements within the Reich.

Margot Lemle reports in her memoirs about the couple’s visit to Palestine in 1937, to explore the possibility of settling there. Two references to this visit to Palestine were published in the Frankfurt community bulletin: a lecture in December 1937 and another in January 1938. Here Lemle, at 28 years old, already reveals himself to be a visionary and not a mere observer: “the ideological presentation of the night was made by Rabbi Dr. H. Lemle on “Poor Promised Land?”, in which he concludes that, in Palestine, we rediscover in a concentrated and exacerbated way all the conflicts and problems of Europe and America. These are the same illnesses and shocks that everyone experiences. Palestine is not a poor Promised Land, but much more a land of contrasts, of sharp contrasts, a land of encounters and syntheses.”

His Chalutzian [pioneer] spirit of closeness to Israel, which he maintained throughout his life, became to the silent listeners a light of hope in the darkness of the Nazi perspective

In the 1979 brochure In Memory of Grand Rabbi Dr. Henrique Lemle, publicist Ernesto Strauss reveals a piece of memory from his childhood: “My brother and I were sitting on the marble steps of Frankfurt’s majestic synagogue, which every Erev Shabbat was packed with people. Among the rabbis was a great attraction, the recently hired Rabbi Dr. Lemle z’l, at the beginning of his career, as Rabbi for the Youth. In short time he had won over young people and adults, with his soft and friendly voice, with words of wisdom, confidence and enthusiasm, always within what the time allowed. One of these Fridays stays in our memory as boys of approximately 10 years old. Rabbi Lemle had returned from a trip to Israel. With enthusiasm, he rejoiced in his visit to the Promised Land. Israel would be the solution to all the misfortune that was already unfolding for the remnants [in Germany]. His Chalutzian [pioneer] spirit of closeness to Israel, which he maintained throughout his life, became to the silent listeners a light of hope in the darkness of the Nazi perspective, which presented increasingly dark shadows.”

In that same brochure, Austregésilo de Athayde says goodbye to his friend the Rabbi, extolling that “his books, his sermons, his teachings, by word and example, consecrate an exceptional figure, who must be included in the history of Judaism as a manifestation of the Divine Presence in our times.”

Both the words of Austregésilo de Athayde and those of Ernesto Strauss confirm Lemle’s existential commitment to his new homeland, Brazil, and his transcendental commitment to his ancestral homeland, Israel. Perhaps Lemle’s relationship with the prophets goes beyond admiration, perhaps a relationship of identification – prophets see light in the darkness.

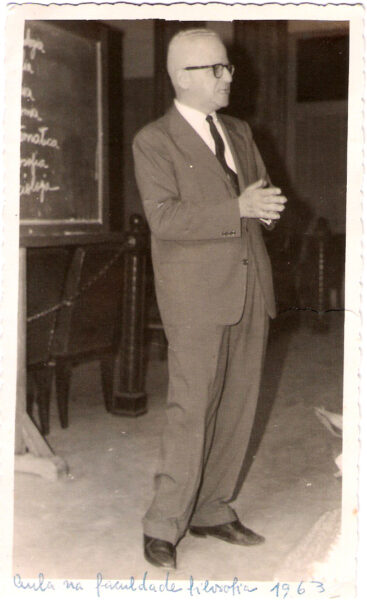

![Dr. Lemle (second, from left) was part of the delegation to the World Jewish Congress, from June 27 to July 6, 1948, in Montreux, Switzerland: “His Chalutzian [pioneer] spirit of closeness to Israel, which he maintained throughout his life, became to the silent listeners a light of hope in the darkness of the Nazi perspective, which presented increasingly dark shadows”](https://www.heritageandhistory.ch/site/wp-content/uploads/2024/03/Lemle_CH_1948_jul_jun_Cong_Jud-1.jpg)